The following article is a reprint of the text: Szostak M. (2019). Frédéric Chopin and the organ, „The Organ”, No 389, August-October 2019, Musical Opinion Ltd, London, ISSN 0030-4883, pp. 30-49.

We encourage you to read the first part of the article: HERE.

_____

Warsaw Conservatory, The Field Cathedral of the Polish Army

We are leaving the white interior of the Lutheran church and going North, passing Saski Park, the Polish National Opera building and some streets of the old town.

In the autumn of 1826, Chopin began a three-year course at the Warsaw Conservatory (then affiliated with Warsaw University), studying music theory and figured bass and composition under Józef Elsner. Figured bass lessons with Elsner were generally held on the organ of the Our Lady of Victory and Saints Prim and Felicien church (today The Field Cathedral of the Polish Army) at Długa Street or on the organ of Piarist Fathers’ palace (no information available)[1].

The place where the Military Cathedral of the Polish Army stands has been devoted to God for three hundred years. By the will of King Władysław IV Waza (1595-1648) in 1642, the Piarist monastery built a small wooden church in the name of Our Lady of Victory. During the Swedish wars, the church burned down. King Jan Kazimierz started the construction of a brick church in Baroque style with a broad name of Our Lady of Victory and Saints Prim and Felicien; the church – designed by Jakub Fontana – was consecrated on the 17th of July, 1701. After the defeat of the November Uprising (1831), the tsarist authorities took vengeance, ordering the monks to leave the monastery and the church. From 1834, the Piarist church became the Orthodox Cathedral and was rebuilt and adapted to the Orthodox liturgy. With the resurrection of Poland in 1918, the church became a Catholic again. On the 5th of February, 1919, Pope Benedict XV appointed a suffrage of the Warsaw bishop Stanisław Gall, the first Polish Army Bishop. The church’s baroque shape was recovered in 1923-1927. During World War II, the insurgent hospital operated in the walls of the Field Department of the Polish Army, which the Nazis bombed on the 20th of August, 1944. The church was rebuilt from wartime destruction, but the garrison remained only by name. Mother of all garrison churches, the Military Cathedral is a temple that became a place of essential events in the life of the Polish nation.

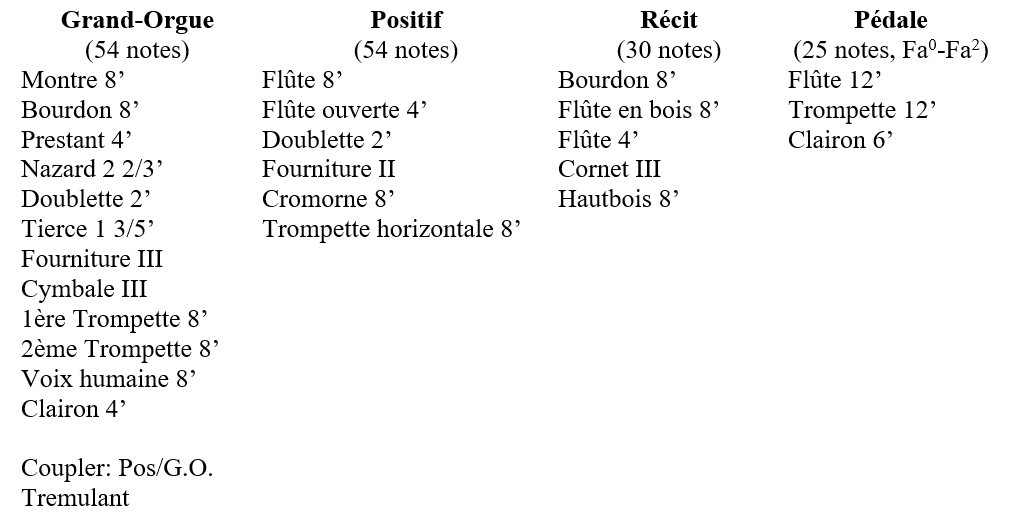

Documents say nothing particular about the organ of Our Lady of Victory and Saints Prim and Felicien church from Chopin’s time. We only know that there was its previous renovation in 1700, and many vocal-instrumental music was performed with this instrument. Although the Orthodox liturgy does not use organs, it is known that in 1885, the organist’s post functioned there; we do not know, however, whether it was an organ or harmonium or whether such an instrument was used in the temple or the rehearsal room. The first well-described organ was a mechanical instrument (30/2M+P) made by the Homan and Jezierski company in 1933. Unfortunately, it was demolished during World War II.[2]

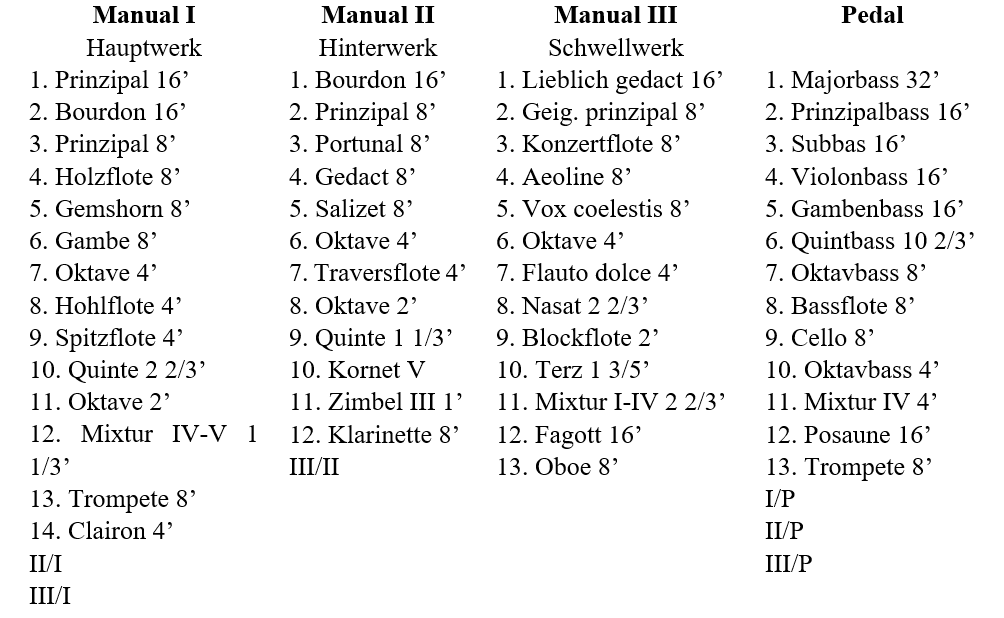

The current instrument was built by Ignacy Mentzel in 1729 for the evangelical church at Landeshut (Kamienna Góra) as a wholly mechanical organ with positive (Rückpositif). On the wave of Romantic tendencies, it was rebuilt two times by Schlag und Söhne (1882) and Sauer (1905). After World War II, the instrument was relocated to Warsaw to the present church, but the Positif section disappeared (it was probably destroyed or sold by the organ builder who took the relocation process). The last rebuild and modification to the symphonic style was taken by the Kamiński Company in 2005. The current instrument has mechanical key action and electric stop action, 52 stops divided on three manuals and a pedalboard, and is one of the best concert organs in Warsaw.

Now, we are leaving Warsaw and travelling 2,5 hours by car to a small village, Obory, located in the northwest of Warsaw near Toruń.

Holidays in the countryside, Obory

In 1824, Frederic finished the fourth grade of the Warsaw Lyceum with a music performance at a public concert[3]. Additionally, he was awarded for “Moribus et Diligentiae / Federici Chopin / in Examine Publico / Lycei Varsaviensis / Die 24. Julia 1824”. This dedication – for morals and attentiveness – embossed in gold letters, is on the cover of the book he received as a reward[4].

At the end of July 1824, Frederic went on a longed-for holiday to the property of the Dziewanowski family in Szafarnia (near Toruń). The owner of the surrounding villages near Szafarnia was Julian Dziewanowski, Dominik’s father. From 1822, Dominik studied at the Warsaw Lyceum; he was a school friend of Frederic and lived on a salary at the Chopin family house for boys. The boys became friends, and after completing their studies in the summer of 1824, they went to Szafarnia for a vacation together. Chopin stayed in this beautifully located estate until September. It was a real country vacation, during which the hosts took care that the young man would provide all kinds of entertainment without forcing him to give up his habits.

In addition to much free time and numerous walks and trips to explore the area, Frederic also had time to exercise or play for pleasure. One of those nearby trips was a visit to the monastery in the village of Obory, about 20 minutes away by horse-drawn carriage from Szafarnia.

The first wooden church in Obory was built in 1605 at the highest peak in the village, thanks to the funds of Łukasz and Anna Rudzowski, and was given over to the Carmelite fathers. Then, the Carmelite convent built a brick church with a tower. The interior – which is still original – was created in the Baroque-Rococo style, decorated with rich paintings and gildings.

Frederic and Dominik, while visiting the monastery and the church, went to the music gallery, where an organ was located. According to the documents, Frederic played on this instrument while Dominik manually pumped the air to the bellows[5].

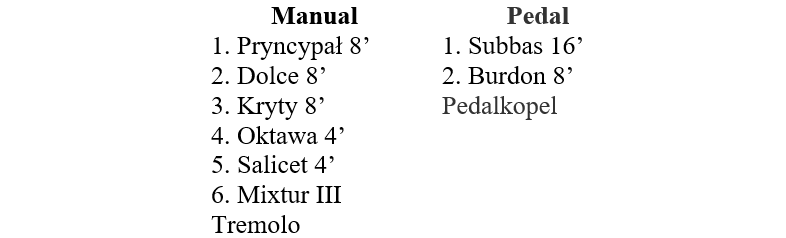

The instrument we find here today is not very distant from Chopin’s time. There is no information about the organ builder. Although it was rebuilt in 1966, and on that date, the windchest was changed from mechanical onto a conical-tubular system, the sound elements and the organ case (still kept in the 18th century, Rococo style) are the same. The organ console is not the same; Chopin played on a mechanical keyboard (with a short octave) built into the organ case; today, the console is free-standing.

The memories of this visit are still alive in Obory church and reminded by the Chopin monument and a commemorative plaque.

We are moving from the village of Obory to Marseille, in the South of France.

Notre-Dame-du-Mont, Marseille

The love affair between Chopin and George Sand (Amantine Aurore Lucile Dupin, 1804-1876, writer) began in the early Summer of 1838. The scandal of their affair and the poor health of Chopin pushed them to spend the Winter in the South. Chopin left Paris on the 27th of October, 1838, and found George Sand four days later in Perpignan. On the 2nd of November, they were in Barcelona, the 7th in Palma, and on the 15th, they moved to Establiments, but he was still ill. On the 15th of December, they settled at the Carthusian monastery of Valdemosa, Mallorca. The climate did not suit him, Chopin did not recover, and Parisian life missed him, but the local population was hostile to them. On the 13th of February, 1839, they embarked in Palma de Mallorca to join Barcelona. The crossing was most painful because of Chopin’s crisis of haemoptysis (pulmonary haemorrhage). They stayed in Marseille to recover the forces of Chopin.

While here, the news of Nourritt’s death in Naples came to their attention. Adolphe Nourrit (1802-1839) – a French operatic tenor, librettist, and composer – was one of the most esteemed opera singers of the 1820s and 1830s; he popularised Schubert’s Lieder in France. The funeral (or Requiem Mass) of a deceased – born in nearby Montpelier – was planned for the 24th of April in Marseille, in the church of Notre-Dame-du-Mont. Both Chopin and Nourritt were popular musicians in their fields, so they knew each other reasonably well. This was the reason why Chopin decided to perform at the funeral mass. We know that Chopin performed an organ transcription of Schubert’s “Die Gestirne” during the Elevation.

George Sand reports that many people were crowding to hear Chopin that the chair was paid fifty centimes. Chopin was not familiar with the technique of playing the organs, and that is why he disappointed crowding people; as a pianist – accustomed to dynamic changes employing fundamental impact – he played with so much gentleness using just one delicate sound “and did not break not two nor three stops of the organ”. At the end of the funeral, Chopin came to see the priest and said, “This organ is worthless; sell it”.

What do we know about the “Chopin” organ of Notre-Dame-du-Mont, Montpellier? It was built by the organ builders Bormes and Gazeau at the beginning of the 19th century in French Classical style. There is no indication concerning its exact situation in this church; probably, it was located on the edge of the gallery, as a “Positif de dos”; keyboards were situated in the back. The upper floor of the case was decorated with sculptures of empire style; the lower case had a set of ornaments moulded in resin, stuck and nailed against the panels. The reed pipe bodies (Trompettes, Clairons, Cromorne, Hautbois, Voix humaine) were entirely constructed of white iron. The white iron reeds have a lively, clear and powerful sound, with a lot of “Bourdon”. Pipes were made of sleeves welded successively and approximately one foot wide; the last sleeve was made of forged lead. This type of reed stop was often met in Italy, but also in Flanders, sometimes in France (Roquemaure) in the 17th or 18th centuries.[6]

Around 1880, the parish – as Chopin suggested – sold the organ to the Notre-Dame-de-Grâce church, Eyguières, a town in the North of Salon de Provence. The instrument was raised on a gallery at the bottom of the nave. This reassembly did not wholly succeed; the arrangement of the instrumental parts suffered modifications for unknown reasons, e.g., the installation of the Pedal pipes was impossible. Around 1920, almost all of the pipework was sold by the priest for the payment of the repair of the church’s ground. Some pipes are, however, protected and stored (the reed pipes of white iron and the facade) in one of the rooms of the presbytery, close to the church. All the instrumental parts, in their entirety, stayed in position until 2009, when the complete reconstruction began and, shortly after that, finished.

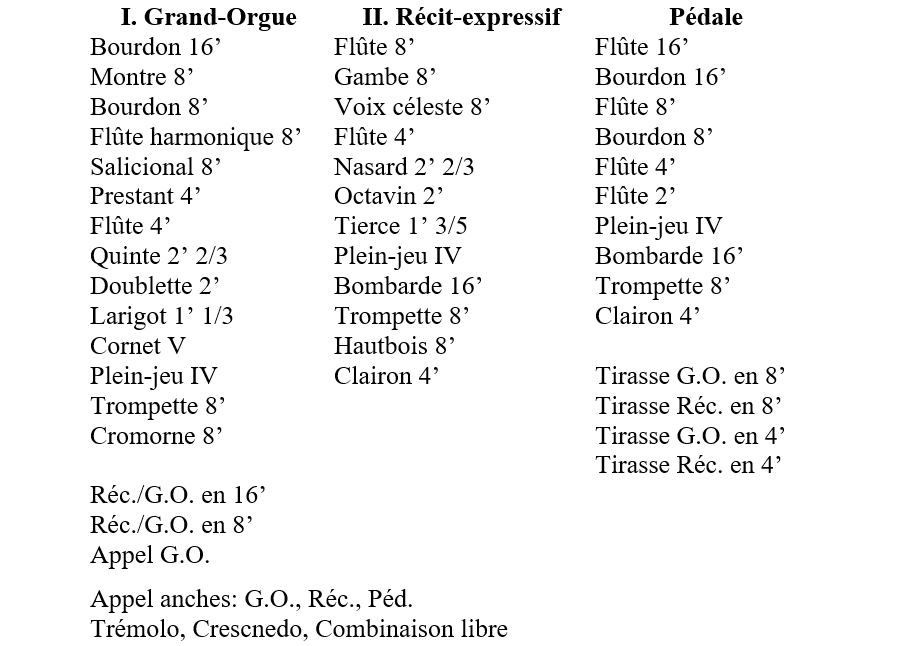

After the sale of the Bormes and Gazeau organ on which Frédéric Chopin played, the Parisian factor Alexandre Ducroquet, the successor of the house Daublaine and Callinet, established at the church of Notre-Dame-du-Mont, Montpellier, a new organ, more adapted to the dimensions of the interior and the aesthetic criteria of the time: two keyboards and a pedalboard. Just a few years later, in 1895, the house Mader-Arnaud of Marseille performed a restoration, added three new stops (Gambe, Voix celeste and Voix humaine) and reviewed the harmonisation. In 1910, a new restoration was entrusted to the Michel-Merklin and Khun factory from Lyon, where a new console was installed. The same factory carried out essential works in 1926. From 1937, the organ was enlarged and modified to a neoclassical aesthetic. It was its last rebuilding, and after that, we were given memorable concerts by the most outstanding performers of the moment. The instrument has been silent since 1970 and is waiting for the next restoration.

Epilogue

On the 30th of October 1849, at the prestigious temple of La Madeleine, many aristocratic personalities of Paris, London, Berlin and Vienna, as well as great musicians, took part in the funeral of Frédéric François Chopin, one of the most famous piano composers and performers but also the most expensive piano teacher in the city. The most influential organist of then France, Louis-James-Alfred Lefébure-Wély, performed on this occasion on the brand new great symphonic Cavaillé-Coll instrument two Chopin’s piano Preludes (No. 4 in E minor and No. 6 in B minor, Op. 25) during the Offertory[7]. The audience was astonished and intensely rushed to hear the music of their beloved piano artist who had left them just a few days before (the 17th of October). The funeral procession to Père Lachaise Cemetery was a dark conduct of sadness and sorrow. Even the most outstanding personalities walked, and their carriages decorated with family coats of arms followed them.

It was not the end; it was just the beginning of the new eternal life of this extraordinary artist.

_____

[1] Gołos Jerzy, “Warszawskie organy”, T II, Fundacja Artibus, Warszawa 2003, pp. 108-109.

[2] Gołos Jerzy, “Warszawskie organy”, T II, Fundacja Artibus, Warszawa 2003, pp. 104-109.

[3] “Gazeta Korespondenta Warszawskiego i Zagranicznego”, No. 128, 1824.

[4] The book was: Monge Gaspard,”Wykład statyki dla użycia szkól wydziałowych i wojewódzkich…”, translated by. O. Lewocki, Warszawa 1820. The original book is in the collections of the Fryderyk Chopin Museum in Warsaw, inv. no. M/381.

[5] Chruściński K., “Chopin w Szafarni i okolicach”, Golub-Dobrzyń 1995.

[6] S.A.R.L Orgues P. Quoirin, Saint-Didier.

[7] Zamoyski Adam, “Chopin. Książę romantyków”, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Warszawa 2010, p. 7.