Paul Zaba: A few years ago, I told one of my teachers that I was working on a piece of music with my friend and former band-mate Sam Kidel, a producer of electronic dance music. My teacher asked why, followed quickly by a much more cutting question: Who stands to gain more from this? I was shocked by the egocentrism and competitiveness which this implied, and answered him with some confused combination of I don’t know and Why not both?

On reflection, this was not a surprising question. Composers tend to work alone. There are many reasons for this, internal and external: no major, international composition prize has ever been awarded to a duo; comissioning fees are often insufficient for a single composer, let alone two; perhaps the traditional model of pen and paper composing itself carries an „in-built” bias for solo creation, as only one person can hold the pen! Of course, in order to realise this notation, performers are needed, and composers relinquish some control when they hand the piece over. But rarely, even in experimental practices, do they admit another composer into the writing process itself.

Traditional models of collaboration often carry an internalised heirarchy: think here of the composer/librettist relationship, with composer clearly „in charge”, higher paid, and carrying greater prestige. Other forms of collaboration, from choreography to moving image, involve artists from a variety of other disciplines, each in charge of their own feifdom.

Luke Deane: Collaborations, both successful and unsuccessful, will always involve discussion between the composer and others involved; nevertheless, it is hard to imagine any composers giving the „final say” on the music to say a librettist or choreographer. The culture of experts can take precedence over the work and cause difficulty in working relationships. Nobody wants to tread on each others’ toes.

This tendency towards interdisciplinary forms of making, then, neglects a much more obvious approach: composing with another composer. It isn’t easy, as co-composition requires more trust (and less ego!) than mere collaboration. That said, more of us should try this uncomposerly way of writing music. I have found it to have some unexpected benefits, both in terms of the work I have co-created, and the changes it has affected in my own way of thinking and being, changes I carry forward with me. In other words: come on in, the water’s fine!

Luke Deane: Coming from an improvising background, I suppose that co-creating music never struck me as that unusual. I think that my first co-composition was more a form of technology sharing: pouring all of my equipment for making and manipulating electronic music onto a table, and plugging it all into similar equipment owned by my new friend and colleague, Richard Stenton. We were a „duo”, immediately secure in the idea of our combined voices sounding as one; only later as our individual practices developed did we even ask the question „what are we each bringing to this project?”.

After a time, I had to concede that collaboration wasn’t appearing in my life by coincidence; I was actively seeking it out. I thrilled in having my mind stretched by a collaborator; at the best of times, there was an almost competitive angle to it. Somehow, I felt that we were always trying to out-do the previous suggestion with a better, deeper one.

In my work, often the form of expression is everything, and co-composition has been an extremely efficient way of finding new ways to express myself. In fact, after a co-composed work, and typically an incredibly long night’s rest filled with intense dreams, I really do feel like a different person. The collectivist and abundant spirit will live on in me for months following a performance, probably resulting in arranging further collaborations. If the music that we make comes from an internal place, or else acts as a mirror, then perhaps it can only really change when we look away from the ego.

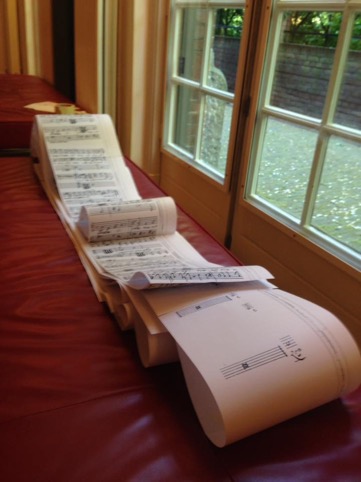

In the spring of 2016, Luke Deane and I began working on the second version of Returning Odysseus, a piece we’d written together the previous year. The piece is a point-of-view realisation of Monteverdi’s late opera, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria. With an onstage camera projecting live video, the musical material and facsimile score of Monteverdi is rearranged and recomposed into a journey across the stage. It was scored for six players (harpischord/organ, trombone, guitar, violin, harp, soprano), and Luke and I performed in the piece ourselves, operating the camera, playing some other instruments, and manipulating the set. The piece contains six sections in different parts of the stage, and the journeys in between them. First off, the camera focuses on a fascimile score of Monteverdi’s opera. We opened the book, and a square hole was visible through one of the pages. Thus began „window”, a strange sort of score-follower, with falling notation cut out of the facsimile, printed onto a 100-metre scroll-score.

„Window”

Photo: Paul Zaba

After this, „tunnel”, in which the camera travelled through a mic’d up tunnel in which we encounter a miniature score which triggered one gasp of sound. Next was „sirens”, in which the melody that Monteverdi’s gave to his chorus of sirens was performed on a WWII air-raid siren, with the female musicians mournfully following in unison. After this, „pathfinder” invited to the audience to „choose their own adventure” across a decision tree of lines of notation, sight-read by the players from the screen. Next, „Argos”, a pile of bones and dirt was played as percussion, while the soprano gave out stylised howls of Odysseus’ miserable dog. Finally, „lightbox” ended the piece with four-channel audio, alongside glowing noteheads, dancing in light. In the process of composing this piece, our decisions became so enmeshed, that in a number of cases, it is now difficult to retrace our steps, and decide who contributed what. This is a good thing.

Photo: Co Broerse

A month after the piece’s premiere in Amterdam in May 2016, I delivered a version of this essay to a composers’ symposium at Birmingham Conservatoire. I had Luke record the following set of rules, to contribute to the talk:

[A trascription of] „Luke’s handy rules for collaborating”[1].

1. Collaboration is about serving an idea, not serving yourself. There is only one idea: can I make a great thing?

I would change this ever so slightly, to read: „can we make a great thing”.

2. Argue. Try to conceptually and practically out-do your collaborator’s ideas at every turn. If you think bigger than them, they’ll think bigger than you.

3. We all know that a tiny musical moment can make a masterpiece. So can two hours of material. There is no such thing as equal time spent on collaboration. Don’t keep track. Only keep track of how good the piece is – constantly.

Co-composition requires good-heartedness. It might be tempting to get annoyed that you’re working harder than the other, or guilty that you’re working less, but both these feelings are a pointless waste of energy and time.

4. Only let an idea go if your collaborator’s idea is better. If it isn’t, just pretend for the moment that you let it go, but secretly think about it all the time, and then weigh it in later. They’ll probably love it.

When I heard this, it really made me laugh, and I immediately thought of a moment in the Returning Odysseus where we would ask the audience to vote between following two different lines of music. Initially when I said this idea to Luke, I didn’t mean it seriously, it was an off-hand remark, a joke. But Luke kept it, weighed it in later, and indeed I acquiesced, came to love it. And if their smiles were anything to go by, the audience did too!

5. Don’t work with negative people. They kill material and ideas for fun.

Though I am in favour of co-composition, I can think of many people I wouldn’t attempt it with. Indeed, our desire to build on the first version of Returning Odysseus was not simply due to the piece’s potential, but more to the potential of our working relationship, and the joy it brought us. It is rare to find someone you can co-compose with so productively – but certainly not as rare as most composers think!

6. Make a deadline; otherwise, you won’t ever finish the collaboration. This is because collaboration is about process.

Luke had written these six out on paper. Rule number seven was more improvised:

and 7 (which is not really a point but something that is quite fun) is to always try and slip in one surprise for your collaborator towards the end. The little details that happen when you’re working so fast on a piece that maybe you didn’t even have time to tell your collaborator that you put something in: that’s all good, that’s all fine. It’s part of the piece expressing itself in the end, after it’s become a kind of meshed consciousness.

As I said before, co-composition requires trust! The two of us were working on our piece right up till the very last moment and, indeed, both of us had unplanned surprises for the other come the performance.

Co-composed works also often manifest as latent snapshots of the collaboration process. One can read in the notation (quite clearly I think) of Returning Odysseus, the many hilarious and beautiful creative exchanges that me and Paul had whilst making it. Just as in a dance between two perfect strangers, in co-composition, the first tentative movement is just as much a part of the dance as the final flourish.

Quite. there is much to be gained from this form of working.

It’s midnight, and I’m finishing this text by torchlight in the back of a car on a campsite. I’m using the last 4G on my phone before the battery dies to tether my computer so I can send this to Paul to make the final proof. Last time I was up at midnight working so hard with Paul, he was sleeping at my feet, as I silently spliced Monteverdi’s facsimile on photoshop, listening to beautiful music and slipping in and out of sleeplessness and delirium. The stars were just as bright, and just as perfect that night, as they are now…

Returning Odysseus

Przypisy:

[1] Luke recorded these rules at a time when we were using the terms „collaboration” and „co-composition” somewhat interchangeably. I feel like we have since become more precise in our deployment of these terms, though Luke disputes this!

Spis treści numeru „Kompozycja Techno-Logiczna”:

Felietony:

Julian Gołosz, Czy Ten Felieton Wywróci Twoje Zdanie O Muzyce Do Góry Nogami?!

Jakub Strużyński, VAPORWAVE – hauntologia, technokultura i kapitalizm

Wywiady:

Tomasz Michałowski, Paulina Zgliniecka, „Gdyby inspiracją była tylko muzyka poważna, to trochę kręcilibyśmy się w kółko” – Rozmowa z Pawłem Malinowskim i Moniką Szpyrką

Ewa Chorościan, „Na co dzień zajmuję się tym, żeby uwrażliwiać odbiorcę” – wywiad z Wojtkiem Blecharzem

Recenzje:

Ewa Chorościan, Każdy z nas jest salą koncertową, czyli „Body-Opera” Wojtka Blecharza

Paulina Zgliniecka, Parametry, analogie, warstwy, sekwencje. O „Metaformie” Pawła Hendricha

Publikacje:

Piotr Peszat, Conscious music

Paweł Malinowski, O utworach z wideo Michaela Beila

Edukatornia:

Aleksandra Flach, Idea pejzażu dźwiękowego Raymonda Murray’a Schafer’a w myśli i twórczości Lidii Zielińskiej

Ewa Chorościan, Jörg Mager – zapomniany wynalazca instrumentów i pionier mikrotonowości

Kosmopolita:

Paul Zaba, Luke Deane, Co-Composition: Radical Collaboration

Paulina Zgliniecka, Międzynarodowe Letnie Kursy Kompozytorskie „SYNTHETIS”

Rekomendacje:

Paulina Zgliniecka, Audio Art Festival

Maria Zarycka, Spółdzielnia Muzyczna Contemporary Ensemble