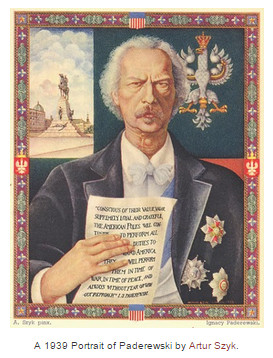

Who were the greatest Chopin performers of all times? I wrote a list, once. (I copied it at the end of this post, for those interested). Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) has a place of honor on my list – not only of Chopin specialists. A great pianist, statesman and a fascinating composer, Paderewski is beloved by Polish Americans, still grateful, after almost a century, for his role in Poland’s regaining independence.

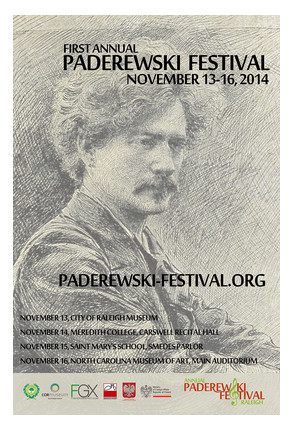

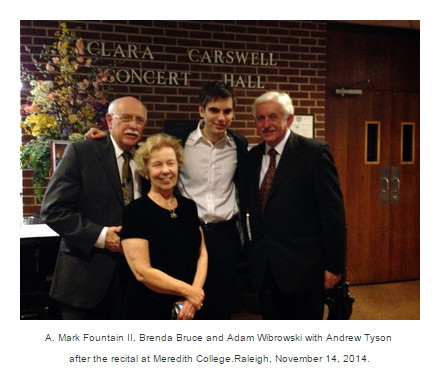

On November 13-16, I had a pleasure of participating in the first Annual Paderewski Festival in Raleigh, organized by Dr. A. Mark Fountain II, President of the Festival and Honorary Consul for Poland for North Carolina, his wife, concert pianist Brenda Bruce, and Artistic Director of the Festival, Adam Wibrowski. There were three concerts and four lectures spread over the four days Festival encompassing, or so it seemed, the entire city: the City Museum, the Meredith College, Smedes Parlor at St. Mary’s School for girls, and the North Carolina Art Museum. All halls were filled to capacity and the audiences included both the local Polonia (with many researchers and professors in biological and engineering professions), and the luminaries of cultural life in the so-called Triangle area – the greater Raleigh-Durham, including Duke University and about 2.2 millions of residents.

Due to work obligations, I missed the first lecture given by Dr. Mark Fountain on November 13, 2014, but I was happy to later attend a „private tour” of this informative and fact-packed introduction to Polish political and social history before Paderewski, and during his life. Dr. Fountain’s doctoral dissertation was about Roman Dmowski, the leader of the National Democracy movement in Poland, both pre-and-post independence. He wrote it at Columbia University, but started his graduate work in history with an intent to study German history. A trip through Poland in the late 1960s changed all that, and the country gained a tremendous friend and advocate. His library of books and old prints features items going back to 1591, and consists of thousands of volumes organized in the largest Polish-themed history library I have seen in a private home (PIASA’s history library may be larger, maybe, just maybe…).

I asked about the „whys” – why Poland? why Paderewski? It’s really quite straightforward, said Mark Fountain, I first came to Poland in 1965 from four weeks of travel by bus through Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union. We had come straight west from Moscow to Warsaw. The difference in culture was so striking that I had to ask „Why?” I’ve been asking that ever since. On the Festival proper, I thank my wife whom I met only twelve years ago. I had done a lot with music, but she is a professional musician; she’d come to Poland by way of Chopin.

The interesting thing about Paderewski and Raleigh – as Dr. Fountain pointed out during his talk – is that the pianist played four times in the area: in 1917, 1923, 1931, and 1939. Each recital was given at a time associated with a major political event. A. Mark Fountain II writes:

The first of these performances occurred on the notable date of January 23, 1917, the day following President Woodrow Wilson’s first public statement in support of a free and independent Poland, a statement made at the express request of Paderewski only a few days before. Almost one year later, on January 8, 1918, President Wilson issued the famous „Fourteen Points” of which the Thirteenth Point expressly provided for a free and independent Poland. The last of Paderewski’s performances in Raleigh occurred April 28, 1939, mere months before Germany invaded Poland and began World War II.

In 1919, Paderewski was Poland’s representative at the Versaille meetings to forge the Peace Treaty after World War I and signed the Treaty along with representatives of European countries and world’s superpowers. Later that year he was elected the third Prime Minister of newly independent Poland, but left the post after a year to return to his music career. It was replaced, again, by political activism when, in 1939, after the start of WWII, he return to touring America to promote the Polish cause. He died along the way, of pneumonia.

There is another connection between Paderewski and Raleigh: a Steinway pianosigned by the great pianist (and personally selected by him) for the secretary of his wife Helena Paderewska, Mrs. Mary Lee McMillan, who returned to her home in Raleigh after years of working for Helena (years that she documented in her memoirs, My Helenka). The Paderewski piano is now found in the music room of Dr. Fountain and his wife, pianist Brenda Bruce. And, yes, it is played daily – as shown in the photograph below. Mark Fountain explains: Brenda is playing on her own Steinway „B” which she purchased in Boston in 1968; Krzysztof Książek is playing on the McMillan Steinway „M” (with the wing up), the piano which Paderewski signed and gave to Mrs. McMillan at 1810 Park Drive, Raleigh, in 1924. A concert grand („B” or „D”) would have overpowered that relatively modest house and would have been completely beyond the capabilities of Mrs. McMillan herself. For more information about Paderewski’s Raleigh and Durham concerts and his piano in Raleigh, please visit the Festival’s website: paderewski-festival.org

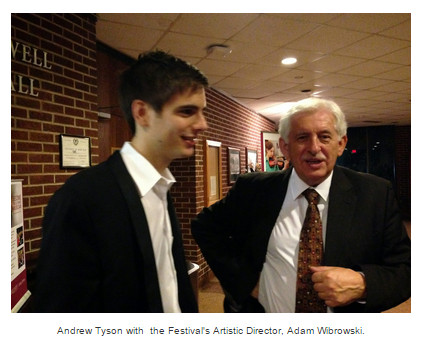

The First of Three Concerts – Andrew Tyson

The heart of the Paderewski Festival was, of course, the music. Not only by Paderewski. Similarly to the Paderewski Competition in Los Angeles, organized every three years by Ignacy Jan Paderewski Society (2010 and 2013 so far), the pianists presented one or two works by Paderewski among a choice of music by others. In this case: Chopin, Liszt, Mozart, and even Dutilleux. Each recital was different and each presented Paderewski’s music and his pianistic achievements in a new light. For the selection of the pianists we have to thank Prof. Adam Wibrowski, who also serves as Artistic Director of the Paderewski Competition and selected two of the 2013 Competition’s winners for presentation in Raleigh. (In Los Angeles, Wibrowski shares his artistic duties with Prof. Wojciech Kocyan, but in Raleigh he makes major musical decisions alone).

Andrew Tyson, a native of nearby Durham, started the concert series on November 13, 2014 at the recital hall of the Meredith College in Raleigh. Tyson, tall, energetic and handsome, has all the makings of the future piano star: impeccable technique, intellect, and expressive power. In short: charisma. His program placed Paderewski’s music in the context of classical „heavy-weights” – Robert Schumann and Henri Dutilleux.

Tyson began his program with two works by Paderewski, Minuet in G Major, Op. 14, No. 1 and Intermezzo Polacco, Op. 14, No. 5, both from a cycle of Humoresques de Concert, Op. 14 of 1887-1888. The Minuet from the first book of the Humoresques, subtitled Cahier I – à l’Antique is Paderewski’s greatest hit, a graceful and virtuosic portrait of the ancient and elegant dance of the aristocracy. By starting the concert from the work that Paderewski typically played at the end, as the last encore after a grueling three-hour recital, Tyson honored the old master with a look backward, through modern lenses. The Chopin section of the recital showed his prowess as an intellectual-virtuoso in four Mazurkas Op. 30 (C Minor, B Minor, D-flat Major, and C-sharp Minor), the Polonaise in C-sharp Minor, Op. 26, No. 1, and the Ballade No. 3 in A-flat, Op. 47. Tyson, who just released a CD of Chopin’s 24 Preludes Op. 28 (on a Zig-Zag label, distributed by Naxos), may be called a Chopin specialist.

The smaller works demonstrated clearly Tyson’s expressive range from melancholy to heroic drama, but his Ballade was the most impressive of his interpretations of Chopin works. Composed in 1841, the Ballade is often associated with Adam Mickiewicz’s literary ballad, Switezianka [The Water Nymph] and praised for its structural and contrapuntal richness. Tyson’s performance highlighted the structural integrity and expressive contrasts of the work, consistently building up its large-scale form. The second part of the recital consisted of non-Polish works by Henri Dutilleux, a 20th-century French composer and Chopin’s contemporary Robert Schumann. The Three Preludes by Dutilleux (of 1973-1988), were the favorite part of the recital identified by many listeners, attracted to their clearly articulated forms and kaleidoscopically rich expressive nuances. The Études Symphoniques, Op. 13 (1834) by Robert Schumann again highlighted Tyson’s ability to construct temporal flow into massive musical architecture. As befits this intellectual of the keyboard, the encore was not an obvious choice for a celebration of Paderewski’s virtuosity: an etude for the left hand by Alexandre Scriabin.

The Second Concert – by Krzysztof Książek

The Paderewski Festival highlighted the talents of the pianists and the beauty of historic Raleigh. The second recital took place at the historic Smedes Parlor on the elegant campus of St. Mary’s School for Girls – a private boarding school filled with international students getting the highest quality of education, including the music of Paderewski. The Festival’s Artistic Director, Adam Wibrowski, opened the event with a lecture about Paderewski’s start of an international career with his debut in Paris, and highlighted the similarity of the 1839 Parlor to aristocratic salons where Chopin himself preferred to perform. (Wibrowski’s first lecture preceded Tyson’s recital and took the audience on a trip back to Poland’s of Paderewski’s youth – in the Russian-ruled area of Podolia, fertile backwaters of European breadbasket, now in Ukraine.) On Saturday afternoon, filled to capacity with modern audiences, the Smedes Parlor, named after the founders of the school, was overflowing with Chopin’s music.

Książek was described by a Raleigh’s reviewer, John Lambert as a no-nonsense player who largely eschews mannerisms too many of our conservatory-produced artists adopt too early in their careers. Indeed, his Raleigh debut was a step on the way to greater things – he is getting ready to submit his recordings to the International Chopin Competition. The 24-year-old pianist has already won many prizes in a variety of competitions around the world, including the second place in the 2013 American Paderewski Competition as well as a special prize for the best interpretation of Paderewski (the competition is held every three years in Los Angeles). After starting the Raleigh recital with Mozart’s Variations on Come un agnello by Giuseppe Sarti, a forgotten aria from a forgotten opera, Książek demonstrated his Chopin credentials with an extensive program including: the Nocturne in F-sharp Minor, Op. 48/2, two Etudes, E Minor, Op. 25/5, and F Major, Op. 10/8), the Fantasia in F Minor. Op. 49) in the first half, followed by the Mazurkas Op. 50 (in G Major, A-flat Major, and C-sharp Minor), the Polonaise in F-sharp Minor, Op. 44, and the A-Flat Major Waltz, Op. 42.

As Lambert observed: These performances were revelatory in terms of the fresh insight the artist brought to them… constantly alive with carefully-controlled infusions of interpretive life that in turn brought the music to vivid life as if emerging from the printed pages for the first time. Indeed, after hearing this young pianist it is hard not to start writing such exorbitant and extravagant expressions of praise. „Revelatory” is the right label for this poet-philosopher of the piano. From the sorrowful, most poignant and tranquil notes of the Mazurkas, to large-scale twist and turns of emotions and form in the Fantasia, to the joie-de-vivre of the Waltz and the tragic heroism of the Polonaise – there was something new and previously unheard-of in each of the Chopin works selected for this journey of re-discovery by Książek. Paderewski’s works were equally original, revealing the depth of expression and abundance of detail in Paderewski’s Variations in A Major, Op. 16, No. 3 and the fantastic, shimmering impressionism of the encore, a Krakowiak from 1884. How could anyone ever doubt Paderewski’s talents as a composer is beyond me – especially after this performance!

The Grand Finale at the North Carolina Museum of Art – by Peter Toth

The Hungarian pianist, Péter Tóth, shared his Los Angeles credentials with Książek, having bested him for the First Prize of the 2013 American Paderewski Competition. I would not have wanted to be in that jury. It must have been extremely hard to decide which pianist should win and which should be the second when faced with two individuals of such obvious, yet different, talents. Toth’s career includes many other competition wins (Wittenberg, Bovino, Weimar and Budapest), recordings and concerts in some of the most important concert halls of the world. On November 16, 2014, the auditorium of the North Carolina Museum of Art became one such site during his recital – due to the quality of the music and its powerful and inspired interpretation.

The recital started with Paderewski – one of his loveliest compositions, Nocturne in B Major, No. 4 in the cycle of Miscellanea, Op. 16. In this work, as Raleigh reviewer Chelsea Hubler writes, the pianist’s „capacity for extreme care and delicacy became apparent” as it was later confirmed in Chopin’s Ballade in G minor, Op. 23. The Ballade, while requiring the subtle tranquility of tone that is among Toth’s trump cards, also showcased his ability to make sweeping, grand gestures of the most romantic kind – all the while keeping his head above the iridescent, fluid waters of the music eloquently streaming from under his fingers to completely engulf the enraptured audience. There. I did it. Purple prose is sometimes the only suitable response to the astounding feats of musicianship that we witnessed during Toth’s recital.

Paderewski’s Polonaise, Op. 9, No. 6 from his set of Polish Dances highlighted the patriotism of the Polish musician that eventually doomed his compositional career – exemplified by writing the monumental Symphony Polonia where the depicting of Poland’s tragic history was more important to him that purely musical considerations, resulting in a work of gargantuan proportions and a grandiose monumentality. Luckily, the Paderewski Polonaise shares little with the Symphony, and, while suitably heroic and dance-like, it ended soon enough to make room for truly monumental Liszt compositions.

Liszt and Chopin were sometimes friends, sometimes rivals, yet their music persists, side by side, known, played, and loved around the world. Toth’s three Liszt selections – Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude (S.173, No. 3), the Legend No. 2 (S.175, No. 2), and the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 – could not be more different and revealed the full diversity of his talents: his titanic virtuosity, a chess-player’s strategic thinking, and brooding romanticism. Liszt was a complex man and an even more complex composer and his music encompasses the musician’s human condition – from virtuosic fireworks to incomprehensibility of religious mysticism. Paderewski himself often played one of Liszt’s Rhapsodies to top off his programs and Toth’s choice is yet another bow to the patron of the Festival.

While thinking of a label for this great pianist, I thought of the „Titan of the Keyboard” – a title bestowed on Paderewski himself, the „Great Immortal”. Toth has issued a critically-acclaimed CD of Liszt’s late piano works (see his website: https://www.petertothpianist.com/) and is among the world’s foremost Liszt specialists. His impeccable technique, intellectualism and profound expression find the best outlet in the equally rich and complicated music of his compatriot. There could be, and were not, any encores after Toth’s rendition of the crowd-rousing Hungarian Rhapsody. But there was an extensive standing ovation. Richly deserved.

I had a pleasure of preceding Toth’s recital with a lecture on Paderewski in the English-speaking world. Given the number of concert tours, and concerts, the thousands of reviews, press mentions, and memorabilia, capturing all of Paderewski’s „triumphs” was an impossible task to perform. Instead of endless statistics (after the initial comparison of nearly 8,000 mentions of Paderewski by the New York Times, with far less frequent notices about such classical greats as Maria Callas, Leopold Stokowski, or Pablo Casals), I decided to focus on Paderewski myth-making and his images. My starting point was the famous „archangel” drawing by Byrne-Jones – created in 1891 and used, in stylized versions, on magazine covers until 1915 and even 1934, the dates of The Etude covers reproduced below. My talk summarized some main points of an article I published in the Polish American Studies in 2010 with illustrations in color. After the presentation, I, too, felt like a star, surrounded by autograph-seekers. Paderewski does this to you. No doubt.

The musical delights and scholarly insights of the Paderewski Festival could take place thanks to an impressive group of supporters, brought together by Adam Wibrowski, Barbara Stann (the Festival’s Board Member and European Liaison), Dr. Mark Fountain and Brenda Bruce and including: Wspolnota Polska, Meredith College, St. Mary’s School, North Carolina Museum of Art, and many private fans of classical music. The support of Ms. Barbara Stann, a Krakow-based pianist was invaluable in spreading the information about this new initiative honoring Paderewski in America. More information about the Festival’s Board of Directors, all of whom ensured that this first annual event was a success, may be found on the Paderewski Festival website.

As it turned out, North Carolina is incredibly beautiful in the fall. Filled with a rainbow of colors, with red, yellow, brown, orange, and green leaves in the famed oak forests, it is also filled with music – that will return in the Paderewski Festival next November.

———————

Sprawozdanie znajduje się też na blogu Autorki: https://chopinwithcherries.blogspot.com/2014/12/chopin-and-paderewski-in-raleigh-nc.html