Len Collins has been a professional musician his entire working life, his career as a guitarist spanned many years and all styles of music. 40 years ago he became a music teacher to share his experiences and to encourage his students to be confident in their knowledge, their ability and, through hard work, maximise their potential.

Marlena Wieczorek: One of the highlights of your career was the Guinness World Record for the world’s largest music lesson held in Milton Keynes, 50 miles north of London, May 2004. Can you tell me more about the event?

Len Collins: The world record hour long lesson in Middleton Hall, Milton Keynes organised by Frankie Parsons and myself, covered the fretboard, scales and modes, chords and even how to hold the plectrum properly. The event was sponsored by Fender guitars, who supplied two electric guitars one signed by The Darkness and the other by Status Quo and both were raffled before the show. Jim Marshall was there signing T-shirts, Chappell of Bond Street, London supplied the sound system, Yamaha donated a guitar for the raffle.

A live concert featuring professional musicians and some of my own students entertained those waiting for the event to start. Officially 211 participants were registered. Confirmation is on page 173 of the 2006 edition of Guinness World Records.

It was a wonderful event enjoyed by all the musicians and raised a lot of money for the MK diabetic association.

M.W.: How do you see your purpose of being a music teacher and what impact do you expect to have on the lives of your students?

L.C.: I see the teacher’s role reaching far beyond a weekly music lesson; as a mentor you are offering life skills, helping to raise expectations and create the right environment for education and discovery. I hope to inspire the essential need to keep studying new aspects of music and the world we live in.

M.W.: You place a lot of emphasis on music reading. The majority of music students learn to read music; some for exams and others for personal progress. Why do you believe there is more to the stave than just playing songs?

L.C.: Reading from the printed sheet is a quick way to learn improvisation. Let me explain: a melody is simply a jumbled up scale, but so is an improvised solo; they are one and the same thing. For example, play a melody in the key of E major then recycle the notes over the same chord sequence and creativity will appear. Trying to improvise from a scale alone isn’t the best way to become a free thinking musician.

M.W.: You created a unique method for sight reading to teach your students to read from the stave quicker than ever before. Your method has been put into practice around the world, including America, Australia and Kenya. Soon it will be taught in the KDF music academy in Uganda. My readers would be interested in knowing how it differs from other methods. How did it come about?

L.C.: Back in 2014 I was with Daniel, a young student about to take his first music exam. His mother confided her worry that he wouldn’t pass the theory section because of his very slow music reading abilities. I sat Daniel down with a pencil and paper. The rest, as they say, is mystery. I don’t know where the idea came from, but he not only passed his exam, he won gold in a music competition a week later.

M.W.: Can you explain the method?

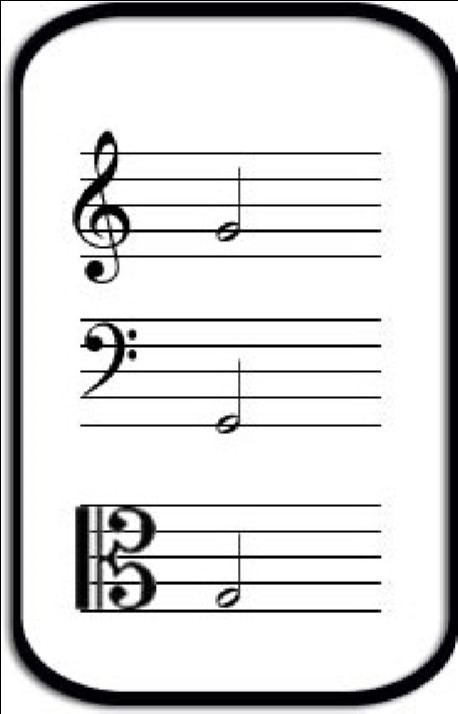

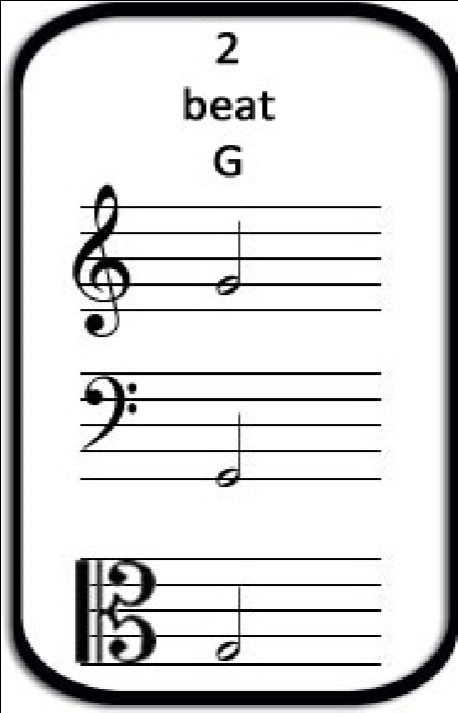

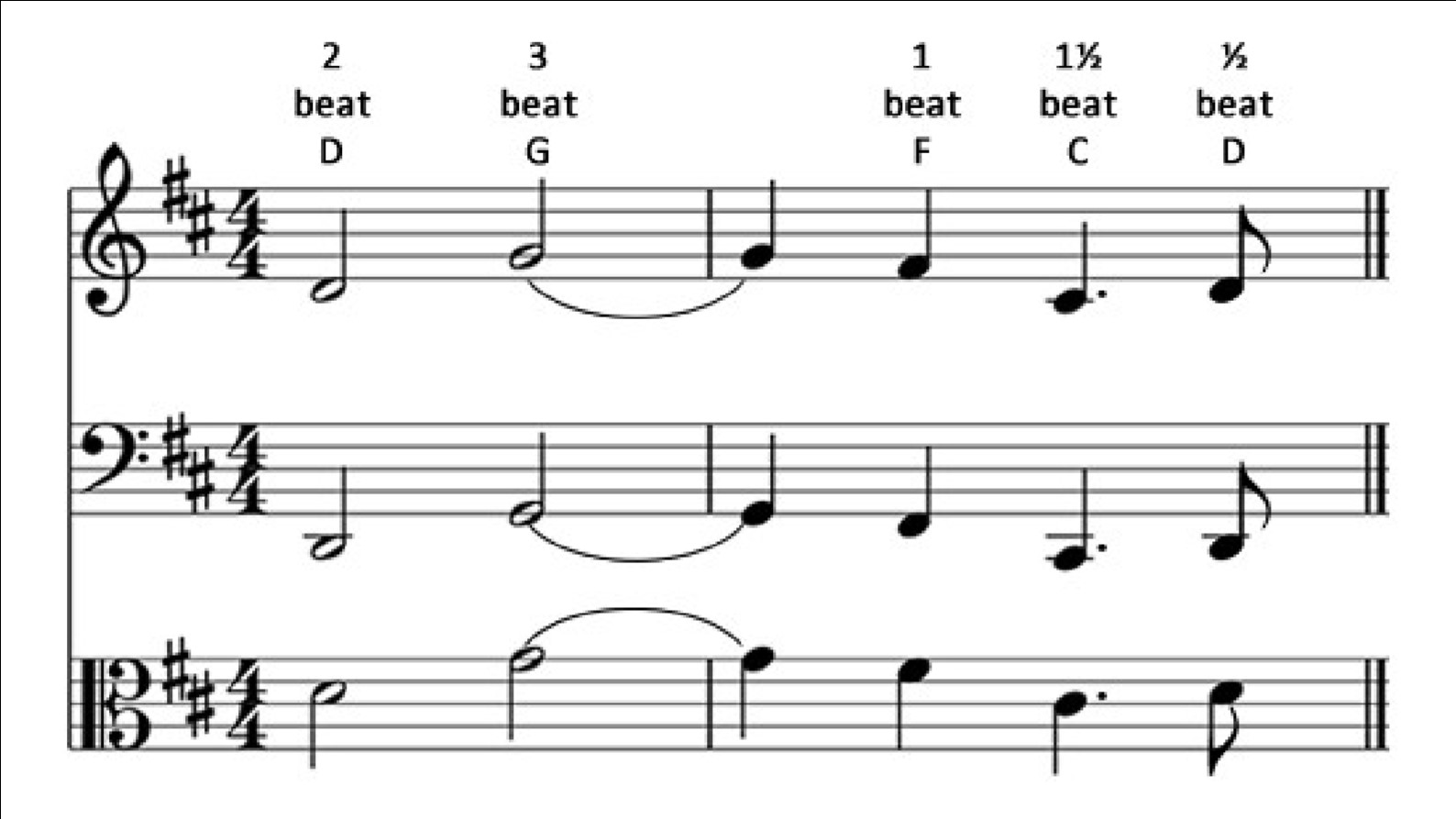

L.C.: When a music student looks at a note on the stave two essential elements must be calculated by the brain simultaneously – the name of the note that needs playing and how long the note is to last for. In the example below the note is a G that lasts for 2 beats

In the next example, using my method, the note is called a 2 beat G; easy for the brain to handle therefore easier to understand and play.

When learning this method I always ask my students to put away their instruments and read the notes aloud until sight reading becomes fluent and usable. It doesn’t take long. A teacher listening to the recital soon recognises when it’s time to sing or play.

In the following example the notes should be read out loud, not played. There is no need to call out the sharps as they are in the key signature.

This works with any piece of music for instrumentalists and vocalists. After establishing a good relationship between brain and stave everything can be put into practice as soon as students are taught where to find the individual notes to be sung or played.

M.W.: Can your method improve other aspects of reading music?

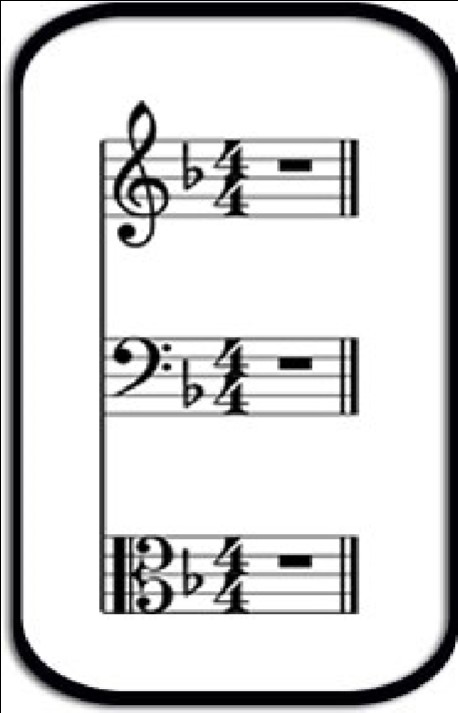

L.C.: Yes, key signatures can be taught the same way by combining the notes in the key signature and the name of the key.

In the example below the key is F major and the B note is played flat.

By reducing the information that enters the brain to its simplest form we call the scale a 1 flat F.

M.W.: What else do you encourage in your method?

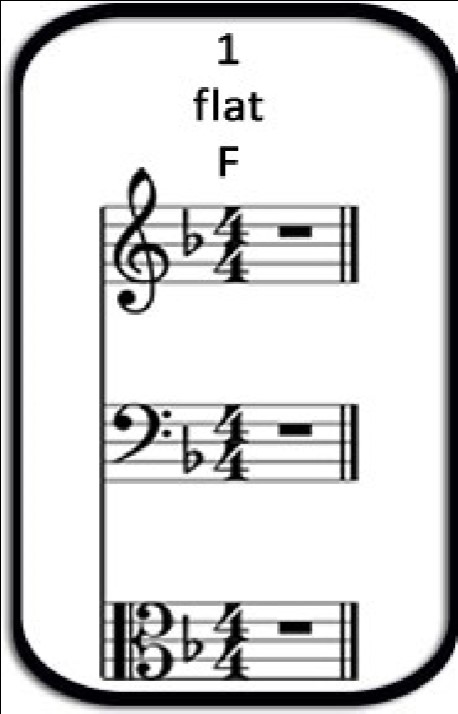

L.C.: I simplify naming the music symbols on the stave; in Europe, a note lasting for four beats is called a Semibreve, in USA a Whole Note. Neither name describes a note lasting for four beats. My students know these labels but refer to this particular timing as a 4 beat note. This is accurate and logical. As teachers we should encourage our music students, not confuse them.

M.W.: Do you ever use the old names?

L.C.: We don’t need the old names, using semibreves, minims, crotchets and quavers is irrelevant in my view.

Trying to remember the name of the symbol and its time value delays reading the music, giving the brain too much to think about. Symbol names based on timing is simply quicker.

However for music exams or working with musicians trained using the old names I ensure my students know them.

This is how I present the symbols.

M.W.: Will reading music before playing or singing be accepted by other music teachers?

L.C.: Yes, if the long term benefits are clearly laid out and the process is quick and enjoyable. Many musicians, young and old, see the notes on the stave as one dimensional, simply a means for playing a song. But it is more than that, it is a foundation from which a musician can be inventive and spontaneous.

M.W.: Your approach to the benefits of reading music will come as a surprise to other music teachers and their students. Will they be keen to follow your example?

L.C.: I hope to change the outlook of music teachers and through them their students. Sight reading from the stave, in a short time, is a reachable goal. When seen as a path leading to enjoyment and freedom of expression the stave will offer encouragement to all instrumentalists and vocalists.

M.W.: What other ways do you improve sight reading music?

L.C.: A beginner just starting out learning to read music will look intently at each individual note, blissfully unaware of the entire phrase waiting to be played. They must understand what the message in a one beat note is. It is vital to look ahead to the next note because if the next event is delayed so too will the next note and the next and panic sets in.

M.W.: How did you become involved with the KDF Academy in Uganda? Could you tell me more about this project?

L.C.: I became involved last year (2020) when the parents of Bethany Kasibo, one of my younger students, invited me to become head of music in the KDF Academy being built in Kachomo, Eastern Uganda. Mike and Elizabeth Kasibo are the founders of the academy.

M.W.: Why did they ask you?

L.C.: Bethany (age 11) sight reads music, combines melody and chords together from a single lead sheet to create instrumental music, she can tell you all the chords that are natural from any given key and will happily explain about the modes the chords came from.

M.W.: They must have been impressed with your methods.

L.C.: They were. It was with great pleasure I accepted the appointment to oversee the development of such a fine project. As Executive Manager of the KDF Music Academy I wrote the curriculum in such a way the young music students in the Kachomo community will first learn to read music before learning to play an instrument or begin singing lessons.

M.W.: Will the KDF Music Academy students in Uganda learn about their music heritage?

L.C.: Elizabeth Kasibo asked me to include The History of African Music in the syllabus. Mr. Olusola Aebiyi, a professional story teller, has written a wonderful piece of work involving music, drama, making wooden instruments and visiting the elders in the local community to hear how they should be played.

M.W.: Has the pandemic made changes to the timescale of the school opening?

L.C.: Sadly, yes. We can’t set a date for the completion of the school, but a lot of work is taking place behind the scenes to raise sponsorship and awareness of the KDF academy and the four departments it will house: music, agriculture, design and technology, and sports. This is the official website I designed for KDF (more about school HERE).

M.W.: You are associated with the MEAKULTURA Foundation’s „Save the Music” social campaign (more about the campaign HERE). What made you feel that it might be a good idea to be a part of it?

L.C.: I am proud to be associated with Save The Music. This initiative reaches into every aspect of social life; where would the world be without the mighty medium of music?

It is recognised that music being played and listened to can have a real important impact on the lives of people living in poverty and help them to find a release from the daily struggle to exist. Musicians around the world raise money for the poorest countries with their performances. But maybe a better solution would be to provide instruments and teachers to encourage young people to supplement their monthly income for their family with music.

A wooden flute, for example, knows no social boundaries. It is at home in a national orchestra or in the hands of a child living in desolate poverty. Education through music is a lifesaver, an inspiration and a life changer. The MEAKULTURA Foundation’s “Save the Music” social campaign will, I know, make a big difference. As a musician and head of music of the KDF Music Academy I applaud what Save The Music is doing.

Partnerem Meakultura.pl jest Fundusz Popierania Twórczości Stowarzyszenia Autorów ZAiKS